In the 1990’s, the Laurelhurst community stood up to University of Washington and said: No more growth.

The university fought back. Its victory in that battle helped turn Seattle into a hub for medical innovation, biotech, and computer science, which in turn made our region what it is today. That’s the story Technology Alliance Executive Director Susannah Malarkey offered in her closing remarks at Xconomy’s Seattle 2035 conference, held this past Friday at Northeastern University’s Seattle graduate campus.

In 2015, as the city faces a new host of growth-related challenges, many of our most innovative companies realize that their continued development depends on the choices we all make as a city about land use and other public policies. Many speakers voiced concerns over affordable housing, transportation, and education. However, only one CEO – Redfin’s Glenn Kelman – took responsibility for his company’s influence on the city.

A comprehensive recap is below. Here’s the TL;DR version:

- Major companies and investors are concerned about Seattle’s long-term livability, meaning: maintaining housing affordability, ensuring we have a transportation system that can handle growth, and not losing our diversity or “middle-class feel.”

- Seattle is home to some pretty incredible innovations in urban sustainability (e.g. the Bullitt Center, the University of Washington’s new Urban@UW initiative), virtual reality, and space exploration.

- Technologists have immense faith in communications, the Internet of Things, and AI to smooth out all the challenges of our future, but are not actively engaged in a corresponding conversation about ethics and the socioeconomic & political dynamics that influence how technology is applied in real life.

That last gap worries me. If we continue to design technology & urban policy as if data/algorithms are magically neutral and immune to the influence of power, we will end up not only replicating, but worsening historical inequities. We already are. While the conference offered few insights for how to turn tech growth into a rising tide that lifts all boats, it offered some unique insights into what’s happening now.

Redfin: Seattle’s looming housing crisis + #Techquity in the end-to-end company

Redfin CEO Glenn Kelman shared his company’s data to illustrate just how close we are to a housing crisis in Seattle – a problem that could temper the gains of our current economic boom and lead us toward a San Francisco-style collapse.

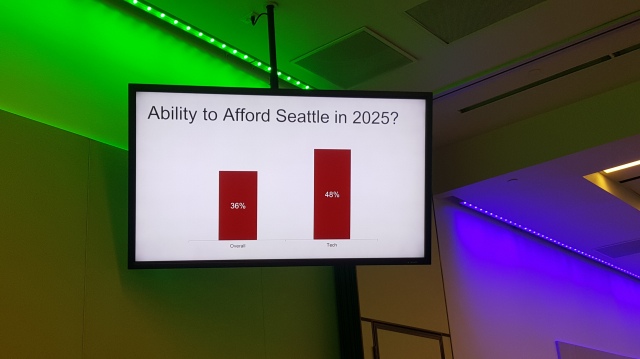

“The only thing growing faster than income in Seattle is housing prices,” Kelman said. For tech workers, cost of living is still reasonable, but even so, the majority of those surveyed by Redfin (including 52 percent of technologists) do not anticipate being able to afford Seattle 20 years from now.

Much of the growth here is driven by Silicon Valley-based companies such as Facebook and Google that are opening engineering offices in other major hubs, from Austin to Portland. Seattle, he says, is the #2 destination after San Francisco for companies and their workers, who are fleeing Silicon Valley in search of more livable cities.

Redfin’s data on what new homeowners prioritize offers some hope for urbanist policy – public transportation and public education rank high on their list – but they are less likely to support new development. High density, Kelman said, is essential to economic mobility. He advocated for land use and zoning that makes it possible for people with all backgrounds and income levels to share neighborhoods, creating the rich network of accidental interactions and economic integration that makes cities great places to live.

“What I loved about Seattle when I came here is that it’s an amazing middle-class place,” he said. Right now, that middle class is disappearing. That is largely due to the way we value labor under present market conditions, with intense competition for a small pool of engineers but little economic incentive to pay fair wages or offer benefits to the contractors who do the work on the other end.

This is crucial now that technology companies are becoming end-to-end companies, delivering both the software and the service. Many of them have set up two-tier systems, in which technologists earn high salaries with benefits, while the people who do the work – think Uber’s drivers and Amazon’s warehouse laborers – are shut out of company gains. At Redfin, the real estate agents have access to the same health care and benefits as the engineers.

“We would be a much more profitable company if we treated our agents differently,” Kelman said, but Redfin is committed to having one culture for all its employees. Kelman also defended the role of Uber & Lyft in building support for public transit, such as buses and bike lanes. He noted that the availability of on-demand car services helps people let go of the idea that they need to own cars, ultimately building support for public transportation.

AI & Equity

Next up was Oren Etzioni from the Allen Institute from Artificial Intelligence. His presentation explicitly pointed out that while computers are great at solving computational problems such as chess games, they are not designed as well to understand what cannot be represented in numbers. He referenced Fei-Fei Li’s recent TED talk on computer vision as an example of how challenging this is. “Problems that we [humans] don’t even know how to formulate,” Etzioni said, “the computer can’t solve.”

Problems that we [humans] don’t even know how to formulate, the computer can’t solve.

Oren’s predictions for 2035 were simple:

1. Driving will be a hobby, not a way of commuting.

2. AI assistants will revolutionize science.

He showed a video of cars moving through an intersection in all directions at once, with no help from drivers or traffic lights, managing a level of chaos with all the aplomb of Cairo drivers. “The algorithm makes sure everyone passes through as efficiently as possible,” he said.

As he spoke, I could not help but think of #listen2mercer. While I would love to share Etzioni’s idealism about technology, I can’t see that working out unless we address the political issues that prevent us from living up to that dream of efficiency. Elites almost always demand priority in transportation systems, such as dedicated lanes (as Mercer Island residents requested, with permanent single-occupant access to HOV lanes just for them) and special vehicle privileges (such as the blue “migalki” that Moscow’s elites used to get through bad traffic).

I asked Etzioni about this afterwards – how we can expect algorithms to fix historical inequity on their own, when history suggests that some drivers would demand privileges denied to others – and I heard what I usually hear: “That’s a good question,” without much to say in response. He acknowledged that we should scrutinize algorithms for their behavior, looking at what values they represent.

I would add to that: We need to consider the impact of algorithms in the real world before deciding whether they are neutral. Mechanisms that are “neutral” on their own can have extremely discriminatory outcomes. In housing, we consider both “disparate treatment” and “disparate impact” to be forms of discrimination, as upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court earlier this year. It’s time that we brought this thinking into the realm of technology as well.

Oren also raised the principle of Amdahl’s law, which applies to non-linear situations, showing that scalability is hindered by increasing complexity. “AI has not and will not increase exponentially,” he said.

It struck me that this concept helps explain why technologists are often vexed by social and political problems. Helping wealthy people is easy – markets exist, and solutions scale. For challenges such as homelessness, war, and refugee crises, there’s no app or magic bullet that will follow the trajectory of Moore’s law. Humanity happens face-to-face, one moment at a time.

Until we recognize this, and invest energy and resources into innovation on social and political problems with the same long-term, persistent, innovative, solution-centric mindset we apply to technological innovation, we will be stuck in the middle of Amdahl’s curve – or, even more likely, slipping down.

Big Data Is So Last Year

The panel, “From Big Data to Machine Learning to AI” started with some discussion on the title itself. Textio CEO Kieran Snyder commented that, 18 months ago, top engineers looking for jobs gravitated toward listings with the keyword “big data.” Roughly 12 months ago, that shifted to “machine learning,” and then 6 months ago, it was “AI.” These are her words–I haven’t seen that data myself and the timeline may be fuzzy, but it was interesting to note.

I was happy to hear Snyder offer a truism I say often: “Data tells us what; it cannot tell us why.” For that, you need an explanatory layer that translates data for humans. For example, data can tell you whether your job listing is appealing to women or not, but you still need someone to help you fix it.

Data tells us what; it cannot tell us why.

That’s assuming the data makes sense to begin with. Socrata CTO Deep Dhillon pointed out that scalability of data analysis is hindered by inconsistent classification. Many of Socrata’s customers are municipalities, whose classification of data in some cases goes all the way back to the pioneer days. There’s a lot of work yet to be done before everyone joins those top engineers on the bleeding edge of technological possibility.

Reality: Augmented, Virtual, Immersive, Mixed, Volumetric, Etc.

Although all the companies represented here–Pluto VR, EnvelopVR, and VRstudios–have VR in the name, each of the panelists said that “Virtual Reality” did not quite capture what their companies were about, but agreed to keep using the familiar term to describe the entire range of what they working on.

Asked to describe their biggest challenge, one panelist said, “Not making people sick.” Built around visual experiences, most available VR has adverse effects on the human body. This flowed into my conversation with some other attendees afterwards. As long as we still live in human bodies and on this planet, we will need clean air, clean water, and healthy food. Even in the future, not everyone will be able to hop into an idealized reality and escape homelessness, domestic violence, or chronic disease.

What About Actual Reality?

The conference then made a welcome shift into the real-world trends that are happening now, briefly focusing on which people and problems are not being addressed by the market.

At lunch, students from Urban@UW showcased their project from the NEXT SEATTLE challenge (where I was a mentor), JobBox. Their project aims to support homeless youth to get and keep jobs. It was a refreshing foray back into the world of the now, and was followed by presentations on the future of agriculture, living buildings, and energy. My biggest takeaway from this combination of panels was the importance of connecting scientists and researchers to one another and to the realities of the world. To quote Nitin Baliga, in an optimized system, “scientists are not just thinking in esoteric ways.” This is where Urban@UW and similar projects shine.

The later panel, “Developing All of Washington’s Talent: What’s Working” offered another solution. Currently, by tapping only the same pool of talent, companies and the industry as a whole are looking at only one set of problems in one way. Infusing diverse perspectives into the work doesn’t just improve team performance, it changes what we work on. Not everyone in our state is a multi-millionaire for whom a functioning self-driving Tesla is the end to transportation woes.

Glowforge CEO Dan Shapiro said, “If we can create companies that look like the world around us, those companies are going to have a strategic advantage.” I hope he’s right. But that’s only true if we continue to have a broad base of consumers.

If we can create companies that look like the world around us, those companies are going to have a strategic advantage.

Right now, the growth of Washington’s tech industry is overlapping with a downward spiral in affordability for those who don’t work in tech. We are creating companies that create products and services only for the small slice of people who can afford them, leaving out the billions of people who lack access to even the basic necessities. We are on a trajectory toward greater inequity. I would modify Shapiro’s comment to say, “If we can create companies that look like the world around us, we’re going to live in a more interesting, vibrant, creative, exciting, livable world.” It will take more than a commitment to the bottom line. It will also take moral courage. I’d like to see more companies like Redfin and Glowforge get into that game.

In the meantime, Ada Developers Academy and Technology Access Foundation have more interest than they can accommodate – ADA Executive Director Cynthia Tee reported more than 300 women applied for just 24 spots in this year’s cohort. There is immense demand for STEM education among our state’s underprivileged. We just have to decide whether we’re going to supply it.

Want to give a company $2000 to own your most sensitive data? Sure you do! Meet Arivale.

The other industry panels were somewhat uninspiring. We heard a 40-minute live informational for a company called Arivale, which for $2000 a year in perpetuity will collect, store, and comment on your most sensitive health data, from your sleep cycles to your blood test results to your genome. The company has no doctors, but promises to pair individuals with coaches.

From a business perspective, this seems brilliant: a platform company, like Uber, for the quantified self. Instead of collecting data in the highly regulated environment of academic research, where participants are typically compensated for their participation and protected by HIPAA and other laws, the company can get people to pay them to collect, store, and analyze their personal health, with (under current regulations on private data) no say in how their data is used.

While this sounds like a great way to deliver returns for ARCH Venture Partners, Arivale’s investor and one of the sponsors for Xconomy’s conference series, it raises a lot of red flags around ethics. Some of my concerns are specific to health, but this also raises another point I’ve been talking about more and more since the start of this year (I saw Irina Raicu speak on this at Town Hall, then ran a breakout section on private sector data at Open Seattle’s International Open Data Day event in February): We’re building an entire economy on the idea that consumer data is a business asset.

So many of the apps we use for free are supported by the perceived value and valuation of our information. That information becomes a business asset that can be traded or shared, claimed by banks in a bankruptcy, acquired in a merger or acquisition, etc. For an example of how troubling this can be, check out this recent post by John Salzarulo on what happened when Homejoy became FlyMaids.

For me, living as I do with one foot in the world of open data/civic tech, this is surreal. With government, we at least have some power to influence both our privacy and our right to know what’s going on. The City of Seattle is currently working on its own open data policy, trying to balance the need for citizen protection with the public’s demand for transparency.

Those principles we apply to government do not yet apply to the private companies who now hold the bulk of our information. What’s more private to you, census data or your credit history? Your voting record or your trip patterns in Uber? What you call your city government for or what you search on Google? Companies such as Airbnb avoid paying taxes and get away with claims that a journalist can knock over in minutes in part by not sharing their data with government (Uber’s arrangement with Boston for emergency planning is one of the only such arrangements I know of in the country).

What’s more private to you, census data or your credit history? Your voting record or your trip patterns in Uber? What you call your city government for or what you search on Google?

If Arivale succeeds in persuading our nation’s wealthy (and/or their employers and insurers) to provide all this data over a lifetime, that could be invaluable for our understanding of how to control risk factors for diabetes, cancer, heart disease, Alzheimer’s, and other common ailments. Do we really want that information only to be available to their paying customers? In the name of economic development and our excitement at spinning up another company (already valued at $34 million), are we willing to look the other way at the ethical issues this raises? There is a way to craft regulatory policy that protects consumers while fostering thriving markets for the care we need most. We simply have not yet done so.

Personally, I would love to have all my health data stored in one place. If I could afford it, I’d love to work with one coach (or at least one entity) over my lifetime. Right now, my records are spread across the planet, in the seven countries in which I’ve received health care, and I don’t think I’ve ever seen the same doctor twice. There are plenty of people like me who could be persuaded that Arivale’s services are worth the cost. But we desperately need better regulation of our most sensitive data first, both to protect us from those who would use it against us and to ensure that its most valuable insights become available to the public.

What’s next for outer space?

The space exploration panel offered fewer takeaways, other than a succinct answer to the question, “What do we need to do to support the space industry in Seattle?” “Fix the traffic.”

One of the panelists dismissed the idea of space debris, saying it’s not much of a problem. I believe him like I believe an oil company downplaying the environmental impact of spills.

I’m looking forward to a more in-depth event the WTIA [full disclosure: they are a client] is hosting tomorrow 11/3 at the Museum of Flight, featuring Korean astronaut Soyeon Yi and speakers from Blue Origin, Space Angels Network, Aerojet Rocketdyne, and BlackSky.

Final thoughts

I was struck by the fact that, when the companies stopped talking about their products and started talking about their needs as businesses, they all pointed to the same concerns about Seattle: housing affordability and livability, transportation, and developing talent.

None of those are issues industry is positioned to solve alone. At heart, they’re about policy and public goods, which have to be paid for somehow. Public education isn’t a consumer good, where you can simply pay for a person’s professional development and then own them for life. At some point, we have to recognize that we’re not going to solve the problems affecting Seattle’s tech industry without significant investment from those who are benefiting from the boom.

As Madrona Venture Group founder and early Amazon investor Tom Alberg mentioned, computer science just became a legitimate course in our school system last summer – but there still are not enough teachers and schools equipped to offer it. While not much movement toward policy advocacy was on display, I was heartened at least to hear that our city’s top tech companies recognize that their future depends at least in part on Seattle’s own.

Check out the hashtag #2035Seattle for more. Thanks to Xconomy, Northeastern University, and sponsors for a thought-provoking day.